This story was originally published on December 2, 2015.

Robin Hammond was working as a photographer for National Geographic in Nigeria when he learned some disturbing news: Five young men had been arrested and publicly flogged. Their crime? Being gay.

"After they had been tortured and lashed with a whip, they had to hide inside the courtroom because some people gathered outside were not satisfied with the verdict. They wanted to stone them to death," Hammond told Refinery29. "Eventually, they escaped that fate, but they were ostracised by their families and had to go into hiding."

Their experiences, and those of many other LGBTIQ people who face persecution around the world, prompted Hammond to start Where Love Is Illegal. His organisation is dedicated to raising awareness and sharing stories of discrimination and survival from around the world.

Hammond said he partners with grassroots organisations on the ground in Africa, Russia, and many places in between to find people who might be willing to share their accounts. So far, the project has made public the stories of more than 65 people in seven different countries. People around the world also share their own portraits via the organisation's Instagram account, which has more than 124,000 followers.

"I don't want the stories just to be about them, but from them as well. It's a very collaborative process. Often, we talk about how they want to be portrayed and they choose for themselves how they want to be seen, what clothes they want to wear, how they want to express themselves. It wasn't just an outsider saying, 'Do this,'" Hammond said of the portraits the organisation takes. "It was the first time for many of them that they had control over how they were heard and how they were seen, and I think that they knew and appreciated that process."

And though many of these survivors' tales are harrowing, violen and difficult, there is hope and joy expressed as well.

"I met people who became stronger because of — in spite of — what they had been through," Hammond said. "Unfortunately, there are 3.8 billion people living in countries where same-sex acts are criminalised, so we have a long, long way to go. But I think the history of countries, including the U.S., has shown that change is really possible."

Ahead, the portraits and stories of people around the world who are fighting back against where love is illegal.

Photo caption: "J" and "Q" are too afraid to reveal their identities. They describe the circumstances they find themselves in: "[We] are a lesbian married couple, though not recognised, because in Ugandan society lesbianism [is viewed] as an abnormality, an outcast, a disease that needs to be cured. We have been attacked verbally by people, by men, who have noticed we are a couple: "You need to be raped to rid you of your stupidity of liking a fellow girl."

Editor's note: Captions have been edited for length and clarity.

"O," 27 (right), and "D," 23

Lesbian couple living in St Petersburg, Russia, 2014

O and D were on their way home after a jazz concert. It was late by the time they got off at their subway stop. They were alone as they went up the escalator to get to the street level, except for two men in front of them. As they travelled up to street level, they took each other’s hand and kissed. They came out of the subway and starting walking home.

Suddenly, O felt a blow to the back of her neck. "Fucking lesbians!" the stranger yelled. He then turned and punched D in the face. O tried to defend her but was punched in the face, too. O screamed, "What are you doing? We are just sisters!" The man replied, "Don't lie, I saw you kissing and you are spreading LGBT propaganda."

The remark was in reference to the "Anti LGBT Propaganda Towards Minors" law recently adopted in Russia. The man continued to kick and punch O and D, screaming, "No LGBT!" Finally, he said, "If I see you again, I will kill you," and then left. All this time, the attacker's colleague was filming the assault with his phone.

Speaking about the assault, O said, "The real fear I experienced was not for myself, it was for the one I love. The fear struck me when I realised I couldn't do anything to protect her…. Now, in Russia, holding hands is dangerous for us. But if the goal of these attackers was to separate us, they failed. They only made our relationship stronger."

Photo: Courtesy of Where Love Is Illegal.

Rihana, 20 (standing, not his real name), with his friend and roommate Kim, 25

Uganda, 2014

In early 2014, Rihana and Kim were evicted by their landlord and severely beaten by the local community. The police intervened and both were arrested and charged with "homosexuality." They spent seven months in prison while awaiting trial.

"We were taken to prison and we had [a] hard life — we were beaten and forced to do hard work," said Rihana. They both complain that they are continuously harassed by the police.

Nisha Ayub, 25

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015

Nisha is a transgender woman. She was arrested and received a three- month prison sentence for cross-dressing, a crime under Malaysia's Shariah law. She was put in the male section of the prison, where she was humiliated daily. That same year, she had gotten breast implants, and she was made to walk topless through the prison. She was regularly verbally and physically abused.

The guards shaved her long hair off, an important part of her female identity. "My hair is my crown, it is my identity, it is the first thing I did when I got my independence — to grow my hair. I was in the chair crying as they cut it. I was begging, 'Please, please, please.' He just ignored me. As each hair dropped, so did my heart."

On her first day in prison, she was forced to perform oral sex on six men. After that, she sought protection from one of the prison guards in return for sex. Said Nisha, "One of the worst things about being in prison is that you don't feel like you own your body anymore. It's like people have the right to do anything to you."

Once released, she found she had lost the job she had in a hotel. In order to get money to survive, she became a hostess in a bar and was forced to perform sexual acts for money. "I heard there was an NGO in Kuala Lumpur helping trans people. When I went to prison, I didn't even know that law existed. When I came out of prison, I was determined to fight, and I wanted to help other trans people. So I went to Kuala Lumpur to volunteer.” Now, Nisha advocates for other transgender women in Malaysia with a nongovernmental organisation.

Darya Volkova, 23

St Petersburg, Russia, 2014

Late one night in the first week of March 2011, Darya was attacked on her way home from a driving lesson. For two months before that, she had received threats on social media. She would receive messages like "Death to lesbians," "Burn in hell!" "If you won't shut up, we will find you!" "We know where you live, we will find you and you will pay for it!" and "We will kill you!"

These were in response to her coming out as a lesbian as well as for her street activism. As she walked through a park on the way home, she heard the footsteps of several people behind her. They shouted for her to stop, but she started walking faster until she came across two men wearing balaclavas blocking her path. She was surrounded. They started to push her and shout "Death to lesbians!" and "Burn in hell!"

One of them threw a punch that she was able to block. Then she felt a powerful blow on her back as one of the men struck her with a baseball bat. She fell to the ground. She was kicked and beaten with baseball bats until she was knocked unconscious. One of the men stabbed her in the stomach. She lay bleeding for what must have been around four hours before she was found.

By that time, she had lost a lot of blood. She was rushed to the hospital for surgery. Several times, her heart stopped. After being discharged from the hospital and spending a week resting, she went to the police. "They just laughed at me…'You got what you deserve, we don’ t serve lesbians here,'" Darya said. She was scared to go back to the area, so she moved away. She still receives threats on social media. No investigation into the attack has ever been made.

"I really hope that destiny will judge them," she said.

Jessy, 24

Beirut, Lebanon 2015

Jessy is a transgender Palestinian woman born in a refugee camp in Lebanon.

"All my life, all of society have treated me in an inhuman way. It got worse as I got older, especially at work and in university. When I was small, my parents saw me playing with a Barbie doll with a girl. They beat me. There are taboos: Boys shouldn’ t play with girls. My father said I was like a donkey, a dog. 'You’re a disgrace,' he said."

Jessy said she knew she was a girl from a young age. "When I was 6 or 7 years old, when my family was away, I used to sit in front of the mirror and put makeup on, like my mum. Sometimes my family caught me — they would insult me and beat me."

From a young age, she also suffered sexual abuse. "My uncle raped me when I was 11 and told me not to tell anyone about this. He raped me three times. I felt destroyed. He was stronger and forced me to do this against my will. I got depressed. It lasted for a long time. It was a very horrible period of my life. He used to tell me it was normal and give me money and told me not to tell anyone. I used to scream and tell him to go away. I couldn't tell anyone about it because no one would believe me because he was this religious person."

Her immediate family did not accept her at all. "My brother has always been ashamed of me. He still is. Many times through my life, he beat me and insulted me. Five or six times, with the support of my father, he tried to kill me. My brother tried to stab me, but he never was able to. Several times, he beat me with a thick piece of wood. Once, my father tried to strangle me, but I managed to escape and run away. I used to go to school with bruises on my face. Teachers would ask me what had happened. I would cry and not say anything. I was afraid."

Students at the school would make fun of her, insulting her and spitting at her. Sexual abuse happened in the school as well. "There was a boy in the school, he was 18, he raped me when I was 15. I was afraid to tell anyone about that. He threatened to tell my family about what happened." But it wasn't just students who were cruel to her. She suffered discrimination throughout her schooling from her teachers as well. At her high school graduation, the director of the school asked her to not attend anymore. "She didn't say why, but she didn't have to," Jessy said.

Jessy went on to nursing school. She thought it would be the one profession that would accept her. She was wrong. "I had studied nursing for one year, but when we were to start the internship, which we must do to graduate, my instructor told me, 'You should change yourself, and change your look if you want to do the internship.' I said, 'I can't change myself. My behaviour and my look is not related to my knowledge and my education.' She then called my parents and told them that they need to change me, and that I should go through spiritual therapy, and I cannot do the internship because my look and my style would damage the reputation of the university."

Without the internship, Jessy could not qualify as a nurse. "I was very down when I realised I would not be able to be a nurse; I got depressed. But then I thought, 'No, I'm not going to give up, I'm going to show her that I will be successful. I will graduate and find a job to show that there are people who can accept me.'

"I've been looking for a job for five years, but when they see me for the interview, they often cancel it…. [One time] I went for an interview, and they said to me 'You're coming to apply here? We can't receive people like you here! We don't even know your gender!' I turned around and left. I felt so humiliated and oppressed."

Jessy has been taking hormones for the past year. She must buy them privately, as they are not covered by the U.N. Refugee Agency (which provides emergency health care only). Due to the fact that she is unable to get a job, in order to survive she's been doing sex work. She is now living her with her mother, who separated from her father six months ago.

One day in 2014, her father came to her mother's house and attacked Jessy: "It was morning, I was still in bed. My father burst into my room, he started shouting at me: 'You have damaged our dignity and our honour!' As he said these words, he raised a broom, which he had in his hand, and beat me with it. I started screaming and all the neighbours came. He threw down the broom and left my room, but he came back immediately with a knife. The neighbours were shouting, 'Kill her and make humanity relieved from her! We don't need these kinds of people in our neighbourhood!' I tried to escape. I thought that someone would help me, but they were all against me. Somehow, I don't know how, I managed to get my clothes and escape.

"I stayed away from the house until my mother called me and told me my father had left the house. This is the tradition. I know he will keep trying, and if he doesn't do it with his own hand, one of the family members will. He still sends me threatening messages." Jessy still lives with her mother and said she feels she has no other choice. "I'm afraid of all the people where I live…. But I was born this way and I will die this way!"

Simon, 22

Uganda, 2014

Simon describes being attacked by the people in his village: "Me and my boyfriend were in our rental room having sex, then one of the neighbours in the next door heard our screams while having sex. He had always suspected me and my boyfriend [are] gay."

Simon said the neighbour then went to the police station, telling the entire neighbourhood as he went about what he suspected was going on in Simon's room. The police arrived with a large number of the other people from the community. They forced open the door.

"[The] police found us all naked and threw us out, handcuffing us. Immediately, the mob started beating us with stones and sticks with nails in them, saying that we were curses and needed to be killed. Later, police took us away through the whole village naked, dragging us through stones, which pierced our bodies and caused severe bleeding. No first aid was given to us and the police threw us in the cells. They told inmates that we were gay, and the inmates started beating us until sleep took them over," Simon said.

"I thank God that I didn't die, because the pain was too much. On the next day, at 10 a.m., we were taken to hospital since we were in a critical condition. When we reached the hospital, the doctor who came to work on us was my former boyfriend, who felt pity for me. At 12 a.m., when the doctor was leaving work, he told me and my boyfriend that he was not going to lock the back door and if any of us had the strength, we could escape and run away. He gave us painkillers to use on or way."

Simon and his boyfriend separated, hoping that they would have a better chance of escape alone. Simon fled to the Ugandan capital of Kampala. He has not seen his boyfriend since.

Sally

Beirut, Lebanon, 2015

Sally is a refugee from Syria but has been in Lebanon for seven months. In Syria, LGBTIQ people have been the target of both government forces and the Islamic State group, or ISIS.

"I ran away from Syria because I was running away from ISIS. One of my family members is now with ISIS. Because of him, I ran away here. He was in charge of investigations in ISIS. They want to catch and kill the gays. My last partner was kidnapped and interrogated by ISIS. I'm 90% sure they killed him. To kill someone, they will choose the highest building and push him from it. They are worse than the Syrian investigation services.

"The gay people are treated as if they have a contagious disease. In Islam, you are given the chance to ask for mercy and to re-enter Islam and follow Islamic law. But ISIS considers gays a contagious disease, so that's why they kill them."

Sally said her kidnapped friend will be forced to name all the LGBT people he knows, including her. Then they will be hunted down. "Some of my other gay friends were captured and stoned to death. One was pushed from the roof of a building, one was shot in the head — just because of their sexuality. They had no proof. In Islam, they say you have to have three witnesses, and [be] caught in action, but they didn't have any. They just killed them because they knew they were gay," she said.

"I can never go back to Syria. The door of my parents' [house] and my country has been shut in my face. If I went back, they would kill me. The regime will take me directly to military service, where I will die. ISIS will execute me, they will throw me from a building."

"On the inside, I'm a woman; from the outside, I don’t know — maybe half-and-half. I'm a woman and not a man, I don't even consider myself a gay person…. I'm planning to do my sex transition," Sally said. She has a short-term job teaching reading classes to refugees to survive, as well as receiving some support from NGOs. She is waiting for resettlement.

Kamarah Apollo, 26, gay activist

Uganda, 2014

Apollo lists the discrimination he has faced: "In 2010, I was chased from school when they found out that I was in relationship with a fellow male student. I was also disowned by my family because of my sexual orientation. I left home with no option but to join sex work for survival and fight for our gay and sex workers' rights because I was working on streets. I was also arrested several times because police officers thought I was promoting homosexual acts in Uganda.

"I have been tortured several times by homophobic people and by police officers. [They have] tied me with ropes and beaten [me], [I have been] pierced by soft pins…a lot of psychological torture by local leaders and police. I can't forget when I was raped in the police cell by prisoners," he said.

"After all that, I decided to start an organisation with some campus students…called Kampuss Liberty Uganda. During the petitioning of the [national] anti-homosexuality act…it became hard for me to find a permanent place to stay because the majority of people are homophobic. I also appeared in local newspapers as a promoter of homosexuals, so right now it's hard for me to get a safe place to rent. I am not working. I was fired from work because I am gay."

Nathalie, 41, (not her real name),

Beirut, Lebanon, 2015

Nathalie describes herself as a woman who used to be a man. "I'm very happy the way I am. I love myself as a girl. I hate people considering me a transsexual, I’m a full girl!" she said.

Nathalie is from Aleppo, Syria. She said she was effeminate as a young man, which caused her many problems, especially when she entered her two-and-a-half years of compulsory military service. She faced regular discrimination and punishment during her enlistment because she was effeminate. At the end of her service, she was imprisoned in a military jail for nine months because her superiors knew she was gay. There, she was tortured.

Back in her hometown of Aleppo, she faced regular discrimination. She became deeply depressed and tried to commit suicide by jumping from the balcony of her apartment. Things were bad before the Syrian Civil War began in 2011, but they got worse when the fighting came to Aleppo. Her house was destroyed in the bombing. There was chaos and people turned on one another.

"No one loved us as a family because of who I am," Nathalie said. People from the LGBT community in Syria started being targeted to a much greater extent. She was deeply affected by the murder of her gay friend. "I knew a gay guy that they caught. This guy was so nice to me. They slaughtered him and placed him in the garbage. When I heard his story…this incident affected me so much. He was my friend. If they could kill him, then we could see everyone would be a target. [The Free Syrian Army] even said on TV they would kill us [the LGBT community.]"

Nathalie and her family decided to leave Syria both because of the bombings and the danger Nathalie felt she was in. "If I was living 1% in ease in Syria, I wouldn't have come here," she said of Lebanon. Her mother has always accepted her for who she is. "My mum is my life, she suffered with me so much. She is like my soul," Nathalie said.

Nathalie now lives in Beirut with her mother and sister. They are hoping to be resettled. "I want someone to hold me, I want a hand on the heart and a country that offers me security. That's what my mum has been to me. I couldn't leave my mum and come alone. I hope this message will reach someone." Nathalie, her mother, and her sister survive on donations and support from NGOs. "I will die before I go back to Syria," she said.

Grisha Zaritovsky, 32

St Petersburg, Russia, 2014

Until 2011, Grisha worked as an after-school theater teacher. Away from work, he was involved in LGBT activism. Few people at his work knew of his sexuality or activism. In October 2011, he was involved in a protest against new homophobic legislation in Russia. Grisha was arrested with one other activist. The police leaked news of his arrest to the media, and it was then reported on Russian news websites. His boss saw one of the media reports.

Three weeks later, his boss asked him to come into the office to discuss the arrest. He was asked to stop teaching and leave the school. He agreed, he said, because some of his colleagues there were gay and Grisha thought that if he fought the decision, they could also get dragged into the issue. Grisha now regrets not fighting harder to keep his job. He is frustrated that as an activist, he puts himself at risk and gets arrested, and yet everything remains the same. Grisha now said he works as a drag queen dancing, singing, and performing stand-up in two different gay clubs in St Petersburg.

Jean Yannick (not his real name), 38

Gabon, 2014

"I left Gabon because I was attacked earlier this year by four guys," Jean said. Jean was stopped while driving on his way home. Four men forced him to take them to his house where, in front of his French partner, they gang-raped him. The next day, Jean went to the police to report the rape.

"We can't help someone like you because our culture doesn't have gay people, and if those people come to kill you, we can't do anything. If you want to be gay, you should leave the country," the police told Jean. The police chief then told Jean to sit down. He took a pair of scissors and cut his shoulder-length hair short.

Jean was then taken to a police cell and kept there for 13 days. He was released with no case opened against his attackers. Jean and his partner went to the French embassy and asked that he be given a visa to enter France. The embassy staff said it would not give Jean refugee status based on the fact that he faced persecution because of his sexuality. Jean's partner encouraged him to go to South Africa, as he didn't need a visa to enter the country and he perceived it as safe for LGBT people. The couple made a plan to meet in South Africa later. They would get married, and then travel to France to live their lives there.

'B,' 32

South Africa, 2014

B is a gay man from Kenya. In 2008, he met David on a beach in Mombasa. "It was love at first sight," B said. That same day, David proposed to B. They decided to meet B's parents so he could come out to them. It was a difficult meeting, full of shouting and arguing. B's parents would not accept his sexuality. B and David decided to go ahead with the wedding. They planned a pre-wedding party.

At 8 p.m., as the party was getting started, they heard shouting from outside: "Kill those shoga [gays]! They are doing what is not African!" B looked out the window to see more than 10 people outside shouting. They were lighting Molotov cocktails. B, David, and their friends ran outside and jumped over the fence to the next building. They looked back to see their house on fire.

The next day, B went to work. While there, he received a phone call from his neighbour telling him David was in the hospital because he had been stabbed in the chest. David was severely injured, but he survived. His family took him from Nairobi to Mombasa. B had to leave his job and went into hiding. He knew he was being looked for.

B had heard that South Africa was a safe place to be. Fearing for his life, he organised his visa as quickly as he could, and flew to Cape Town. Life in South Africa was not easy, however. B faced xenophobic and homophobic abuse. His work permit expired while he was ill, and the South African government has refused to renew it. B now lives in poverty in a tin shack in a township in Cape Town. He said he frequently dreams about David.

Olwetu, 20 (left), with her partner, Ntombozuko, 31

South Africa, 2014

Olwetu and Ntombozuko said that they face verbal abuse every day in the South African township of Khayelitsha. They are called tomboys and witches. Twice, Ntombozuko has been violently attacked because of her sexuality.

The first time was in 2010, when, late one night, she was out with her friends. A group of drunken men started shouting at her and her companions: "Here's these bitches trying to steal our girls." The three men then attacked them. Ntombozuko was knocked to the ground and beaten. Her friends were beaten as well.

The second time, in 2013, Ntombozuko was walking home late one night when a group of men surrounded her and attacked her. A car came down the road, and the men ran. It was then that she saw the blood on her shirt. She survived the attack but lives in fear of the streets that are just outside her front door: "Even now, I'm not feeling safe when I walk in the street." She said the love of her partner has helped her to recover from the pain. They have been together eight months and hope to marry.

Abinaya Jayaraman, 33

Malaysia

Abinaya is a transgender woman. Until the age of 19, she always considered herself a normal boy. It wasn't until her late teens, when other boys started to isolate her, that she started to question herself. She said she Googled "a man with female character" and started to learn about the transgender community. She went to see a doctor, who told her she had a female's soul trapped in a male's body.

At first, she strongly rejected the idea. She wanted to tell her mother, but Abinaya is from a very strict family and didn't think it was possible. "I was so scared to tell her, and I started to cut my arm due to depression. I used to hate myself, and I used to hate God: 'Why did you create me this way?' It took me more than three years to accept who I am," she said. "Then I started to dress up in the house. And I would see my mum's saris and think: 'When will it be my turn to wear that?'"

In June 2008, she told her mother, "Ma, I'm not a boy. I'm a girl, please understand." Abinaya’ s mother slapped her in the face and walked away. One evening in 2009, she said she came home from work and "all my relatives were there. I asked, 'What's going on?' My mother told me, 'We're going to look for a wife for you.' I was shocked."

Abinaya's relatives tried to introduce her to a woman. Abinaya met her bride-to-be and told her, "Look, I can't marry you," then explained everything. But the pressure from her family continued. Finally, Abinaya felt she couldn't take it any longer. In April 2009, she took a cocktail of sleeping pills and painkillers in an attempt to end her life. She ended up in a hospital for three months. Her mother didn't visit her once.

Abinaya’ s family continued to refuse to accept her gender identity. She was disowned and thrown out of the house. Abinaya worked in corporate banking but couldn't reconcile having to act like a man. Eventually, she quit. Without a job and support, she couldn't pay the rent.

"I didn't have a home and no one [was] willing to help me. I approached another transgender woman for help. She showed me the street. And that's how I survived. I’m still doing it. I have to. I’m homeless and jobless. I have no choice. If I had the chance, I would leave Malaysia. I [would] go somewhere where I can live and earn with dignity."

Funeka Soldaat, 53

South Africa, 2014

Funeka heads Free Gender, a Black lesbian organisation working to end homophobia that is based in Khaylitsha, a township in Cape Town. Explaining why they formed the group, Funeka said, "We had to fight or die; we didn't have a choice." Funeka is also a survivor of sexual violence. She said she was targeted because of her sexuality in what the media frequently calls "corrective rape," the sexual assault of gay men and lesbians to "cure" them of their sexuality.

Her attacker was never convicted. She also survived being stabbed in the back multiple times. The attack landed her in an intensive-care unit. "When I hear of someone being stabbed, I still feel the pain," she said.

Shelah, 40

Malaysia, 2015

Shelah is a drag performer and human-rights advocate living in Kuala Lumpur. She was a radio presenter for BFM, a business radio station, before she was prevented from broadcasting after the station received complaints from the Censorship Commission. "They still haven't told me why I was taken off the air," Shelah said. She is now asked to perform for corporate events, but would never be allowed on national television.

"In some respects, things are going backwards. There are sectors of the Malay community that look at the LGBT community as a big no-no…. There is no differentiation in the minds of politicians between Malay and Islam. They feel like LGBT people are a challenge to the Malay identity. The funny thing is that 20 years ago, drag queens were visible. Malaysia is in the middle of a racial, political, sexual-identity crisis…. We are not fighting for LGBT issues, we're fighting for basic human rights, for the right to be!” Shelah said.

Shelah, who goes by Edwin during the day, was a committee member of Seksualiti Merdeka, an LGBT movement. The group was made up of individuals and NGOs around Malaysia that provided a safe and open space for people to share their stories and learn about their legal rights, safe sex, and police discrimination.

In 2011, Seksualiti Merdeka's festival was labeled by the media and politicians as "The Sex Club" and officially banned. Two truckloads of police came to the festival to enforce the ban. Since then, Seksualiti Merdeka has not been able to meet. Said Shelah, "It's very upsetting. I thought I had found my own safe space. It's painful when you see something of such great potential breaking down."

Amanda (not her real name)

South Africa, 2014

Amanda has survived violent homophobic attacks on three occasions. All of the assaults took place in Cape Town townships. One resulted in Amanda's leg being broken. In another, she fended off a man who attempted to rape her. On all three occasions, homophobic abuse was thrown at her and used as a justification for the attack.

"You must stop acting like a man," one attacker said. "You are taking our girlfriends. You don't have a dick. It's a piece of shit [what] you are doing. Come, let me show you, because you never got [sex]," another attacker told her.

Said Amanda, "My best friend was raped and killed because she was a lesbian. [Her rapist] knew she was going to tell. So he killed her. I'm afraid every night. I don't know if there is someone out there waiting for me. I don't trust any men. It seems to me they are all the same: They may seem friendly, but inside they are full of evil."

Boniwe Tyatyeka, holding a photo of her daughter Nontsikelelo Tyatyeka

South Africa, 2014

Nontsikelelo disappeared on September 7, 2010. A year later, on September 9, her decomposed body was found in the dustbin of a neighbour. She had been raped, beaten on the head, and strangled to death. The killer (the neighbour whose bin in which her body was found) said he did it to "change" her. She was a lesbian.

Brice, 25

Yaounde, Cameroon, 2014

In 2012, Brice was living with his mother. One evening, his mother arrived home from work and said angrily to him, "They just called me and told me that you are gay! Is that true?" Brice did not reply. His brother, who knew he was gay, confirmed it to his mother. That same day, his mother took him to an evangelist to "deliver you from the spirit of homosexuality." He was brought in front of the entire congregation by the pastor "to be delivered."

"Spirit of homosexuality, come out of this boy!" the pastor said, and pushed Brice to the ground. As he fell down, the pastor cried, "Thanks to the Lord, he is delivered!" To keep his mother happy, Brice went along with the performance. When he returned home with his mother, she asked him, "Do you feel free?" He told her that nothing had changed; the performance, to him, felt like a scene from a movie.

The next day, she took him to a Catholic priest. There, the priest accused Brice of being a devil. Brice got angry and left. The priest told Brice’s mother that mother and son needed to pray together. His mother continued to pressure Brice, in the name of God, to change. No amount of prayer altered her son’s sexuality. His mother gave up and said, "You have to choose — either change or leave!"

Brice didn't consider this as a choice he could make. He always knew he was gay. He felt he had no option but to leave. "Since you have chosen to be gay, never contact me again!" his mother said. Brice has not spoken to her since. "I'm no longer close to my mother or some of my sisters. Maybe this is the price I have to pay for being gay," he said.

Mitch Yusmar, 47, with his partner, Lalita Abdullah, 39, and their adopted children Izzy, 9, and Daniya, 3

Malaysia, 2015

Mitch is a transgender man and the senior manager of Seed, a nonprofit that caters to the needs of homeless people in Kuala Lumpur. Lalita is the regional learning-and-development manager for an oil and gas company. Their relationship is not legally recognised, so they live with the insecurity that their family could be torn apart should something happen to Lalita, who is the only recognised parent.

Ndongo Alice, 37, holding a portrait of her brother, LGBT activist and journalist Eric Lembembe

Yaounde, Cameroon, 2014

Alice and Eric were very close when they were growing up. There was gossip in the family about his sexuality, but Eric was never open about being gay. Eric was an outspoken campaigner for LGBT rights in Cameroon and critical of state-sponsored discrimination.

Eric was murdered in July 2013. He had been brutally tortured. His legs, arms, and neck were broken. He had burns on his body from an iron. The corners of his mouth were sliced, and his eyes and his tongue had been gouged. Eric's killer has never been caught.

Before his death, Eric had told Alice that he had many problems, but he refused to share them with her. After his death, Alice found out he had been threatened many times. After Eric's death, Alice also received threats. One text message sent to her read: "You will die like your fag brother." Eric's murder has profoundly affected the family. "By losing Eric, we have also lost our mother. She has changed completely — her health, everything. And I feel really lonely without him. He was really helping me," Alice said.

Artyom, 21

St Petersburg, Russia, 2014

Artyom always knew he was different but didn't accept that he was gay until his second year of university. From the age of 12, he said he was teased and beaten by other students because he acted and spoke effeminately. The bullying was ignored by teachers. Artyom had no friends. By 16, the name-calling, physical violence, intense feeling of isolation, and the breakup of his parents' marriage had driven him to contemplate suicide. "I just wanted to disappear," he said.

Artyom considered overdosing himself with medication. Thoughts of leaving his mother all alone stopped him. He denied even to himself that he was gay until his second year in university, when he finally came out to himself. Artyom feels much freer now that he knows he is not alone and has discovered he can be liked by others. He is currently training to be a model.

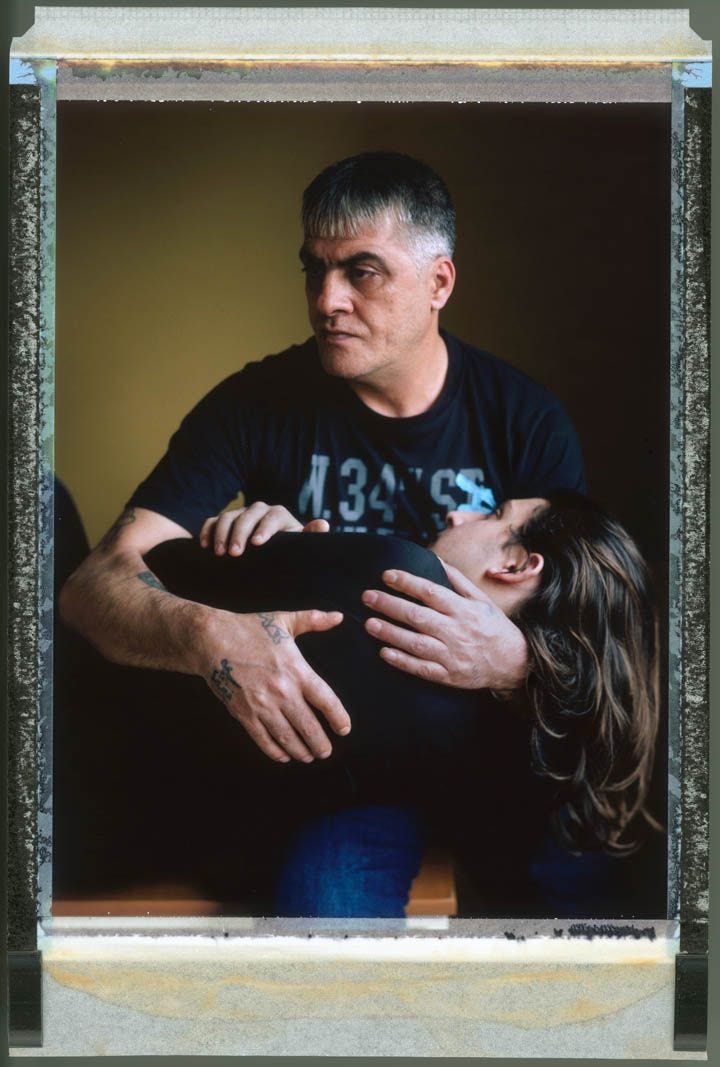

Sari, 20 (lying down), with his partner, Abou El Kheir, 45

Beirut, Lebanon, 2015

Sari came to Lebanon from the Syrian city of Hammmah in August of 2015.

"I was living with my grandparents until I was 7. Then I went to live with my father, who had remarried. One night, when I was 10, it was a summer's night, I woke up to find my father raping me. He raped me 10 times over the course of a couple of years. My stepmother saw me once being raped. I didn't say anything, but still my father turned on me and started to hate me. He beat me, and called me bad names. He treated me like I was a maid. I stayed until I was 15, and then I went back to my grandparents' place. All my family was against me. I was living under the mask, because I didn't want them to know I was gay," Sari said. "I felt like everyone was against me, I was scared that they would find out my sexuality and I would be killed immediately. I had no idea what was gay and what was straight, but I had this feeling I was different, I knew I was attracted to men when I was young.

"My last three years in Syria were terrible because the war started. It didn't affect my life directly — I was an hour from the fighting — but it affected me emotionally. And we were afraid because every day we would hear rumours that the war would come to the city." Sari moved to Lebanon to live with his mother, but the relationship with his mother’s husband was not good and he was thrown out of the house. He spent four days on the streets of Beirut.

"I first knew the term 'gay' when I met Abou El Kheir. In that moment, I had a good feeling: I'm not alone and there are a lot of people who are gay. When I was in Syria, I had short hair; when I came to Lebanon, I grew my hair long. Now, I am afraid that if my uncles on my mother’s side find out I am gay, I'm afraid they will kill me. I told my mother and my grandmother that I am gay so that I can travel to be resettled," Sari said.

"I will never go back to Syria. No way! First, because I found the love of my life here, and the people I really want to be with. But [also], I can't go back to Syria. I would be in danger from the regime, from ISIS, from my family. And no one will accept me like I am now. To be gay in Syria is not at all acceptable."

Read the full story of Sari's partner, Abou El Kheir, here.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

This Sunbathing Calculator Tells You How Long You Can Safely Spend In The Sun

J Lo Says Men Are 'Useless' Before 33 & Here's What Guys Have To Say About It

Strong & Powerful Or Glam & Gorgeous: How Shower Gel Got Sexist